This blog is not an attempt to describe a detailed chronological history of humankind. There are great places to read about this, but this isn’t one of them.

Here I attempt to give a brief overview of some of the significant events that are responsible for our biological and social evolution, designed to highlight that we are the way we are – and therefore we eat the way we eat – for a reason.

Humans (homo-sapiens) have been on the planet for between 100,000 to 250,000 years.

Before we built settlements and houses to keep us warm and provide an ongoing source of food, we had an internal mechanism to ensure our survival. During the significant periods of famine, cold nights and winters, our ability to store fat was a significant advantage in the game of ‘surviving’. It helped keep us warm and acted as a source of energy when food was scarce. Being good at storing fat was a significant evolutionary advantage.

Plainly speaking, people who could store fat better, lived long enough to have children and look after them. The body’s physical ability to store fat is still there!

The only problem is, food is much more readily available, and in the western world we are not subject to the same periods of famine that we once were.

This is one of many reasons that our bodies are set up to gain weight easily and lose it very slowly. We like sweet, fatty and salty foods. The taste is a motivator for us to want to eat more in order to store fat for periods when food will be scarce in the future.

Unfortunately, this desire for these things has not adapted as these foods have become more readily available. On an evolutionary timescale, the change from scarcity to abundance in fatty, salty and sugary foods is the mere blink of an eye, whilst the evolution in humans happens very slowly, due to our long lifecycle.

Evolution happens in the passing on of genes, which mutate, and these mutations are either beneficial for survival or not. Our long life cycle means the rate of mutation is slow when compared with some other animals or insects who have a short life cycle and therefore adapt to their environment much quicker through evolution.

The agricultural revolution that took place around 12,500 years ago, and over the course of a few hundred or a couple of thousand years, we were in a position to create sophisticated tools for farming, and dwellings. Being able to prepare and cook foods allowed us to be able to extract more calories from foods more efficiently, made them safer to eat, easier to digest, and hugely varied.

Without wishing to wash over a hugely important period in human history, I am going to fast forward to the industrial revolution. The technological and societal advances in this period won’t help to explain where you personally are right now.

So…in the Industrial Revolution people no longer owned the means of production, they were merely small parts of a large machine that were all working towards one aim – to produce ‘a thing’, in return for a wage. Large numbers of people moved to (what became) towns and cities in order to work for someone, and this contributed to the strengthening of class-based society – I’ll get into obesity and social class in another blog.

Jump forward to the latter half of the 20th century, following World War II and we see the beginnings of the modern world that exists today. Mc Donald’s began in the mid 50’s and there are now approximately 38,000 stores worldwide. This explosion of fast food has been accompanied over by a decrease in the labour requirements across all industries and within the home, and the increase of labour-saving devices (washing machines, dishwashers, etc.) and sedentary leisure goods (TV’s, computers, etc.) have created an environment in which it is easy to gain weight, and harder and harder to lose it.

Over time, this has a significant effect. It has a disproportionate effect on people with less income. In the least affluent areas in the UK you are twice as likely to be obese as an adult or a child than in the most affluent areas.

Energy dense foods became easily accessible and cheap too as the means of production became a lot more efficient & cheaper. We no longer have to rely on seasonality to dictate what we ate since we were able to get most, if not all foods all year round.

Ultimately, we have largely become completely disconnected from the food chain and methods of production and we have gradually become less able to cook.

I know, your mum is an amazing cook. Your partner is a dab hand in the kitchen too.

This may be the story for you. However, for many people, as home economics and food technology was downgraded in the schools in preference for academic or vocational subjects, we created a nation of people who, at best, learned how to make a few cakes, pizza and scones, and at worst, learned nothing of any use in the real world in how to plan, prep, cook and eat a healthy diet.

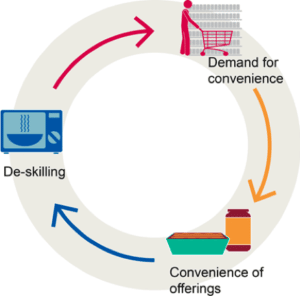

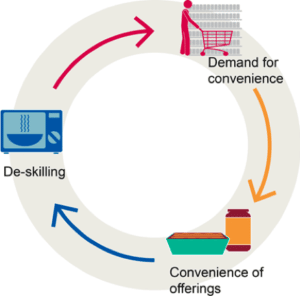

This has created a social evolutionary pressure towards deskilling the population in what systems scientists call a ‘feedback loop’. The 2019 Public Health England guidance relating to a Whole Systems Approach to Obesity provides the following basic example of a feedback loop:

Over time, feedback loops such as the one above gradually create the conditions that we see today that prevent people from having the skills to make healthy choices. Without the skills, they are unlikely to try or be used to spending the time it takes to prepare healthy foods from scratch. People require more convenience foods. Supermarkets stock more of the convenience foods in line with popularity in the markets. When people then do try to change their behaviour and begin cooking healthy foods from scratch, it is more expensive and the amount of effort seems stark and not worth it compared to the alternative convenience options. It is easy to see how many feedback loops can and have formed in society to get us to this point.

The energy dense foods described above are now so cheap and easily available there is almost no limit on the amount of calories you could consume if you chose to. But the issue with them being so easily available is only a problem if you choose to buy and eat them, right? Just because they are in the stores doesn’t mean that you have to buy them? Just because it is in the house doesn’t mean you have to eat them?

Well, yes, in theory, but that just isn’t how humans usually work!

Marketers are tapping into the conscious and subconscious drivers of our behaviour and hijacking it for commercial gain. We’re bombarded every minute of every day with attractive packaging, catchy slogans and health messages, all designed to make us consumer more.

So. We are where we are – and what next?

Starting to unpick these evolutionary habits at an individual level is what we at BeeZee Bodies do every day. It’s not easy, and it’s not quick, but it’s a process that involves tough conversations, developing self-awareness, and then taking responsibility and beginning the process of using the ‘Habit before the Habit’ methodology; running experiments to find new healthy habits that will stick for the long term.

Quick fix, won’t work – these behaviours are in-built. But with the right support, at the right time (when the individual is ready to change), it’s absolutely possible to re-train some of our most in-built evolutionary instincts.

At a societal level there is huge amount of work to do, and a Whole Systems Approach is the only way to turn the tide on our obesity epidemic. That’s for another blog!

Sources and other articles of interest:

- PHE, Diet, Obesity and Physical Activity Team (2019) Whole systems approach to obesity. A guide to support local approaches to promoting a healthy weight. PHE. England

- Series of books by Yuval Noah Harari – Sapiens, Home Deus, and 21 Lessons for the 21st Century